Amber Tuccaro, a 20-year-old single Mum from Alta, Canada, went missing in 2010.

She was last seen alive hitching a ride to the city of Edmonton. Her remains were found two years later in a nearby wood.

Her killer was never found, and no one was ever jailed for her brutal murder.

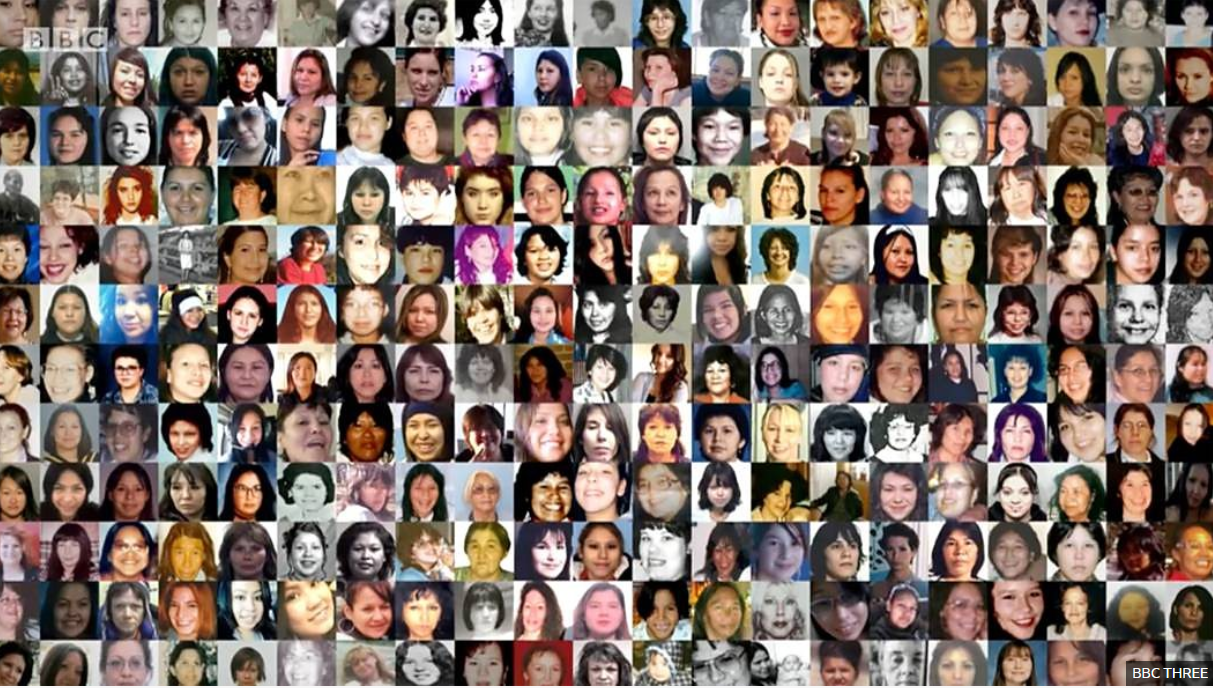

Amber is just one of 1,200 women Canadian police believe have gone missing or been murdered since 1980. Other estimates put that figure as high as 4,000. (note: this was posted in 2019).

What happened to them all?

The mystery is the subject of Stacey Dooley’s new BBC Three documentary, Canada’s Lost Girls.

Amber Tuccaro left behind her 14-month-old son, Jacob. “They didn’t give a sh*t, they didn’t care,” says her mother, Vivian, through tears.

The police took several days to put Amber on the missing persons list, meaning vital clues were lost. They took so long to track down the CCTV footage it’s believed to have been taped over, and an audio recording of Amber in a car with an unknown man wasn’t released until two years after her disappearance.

Amber’s brother says: “I think it was because my sister was Indian. They thought, ‘we don’t have to work as hard on this’.”

They believe their daughter was the victim of systemic racism towards indigenous Canadians within the police force.

Canada’s indigenous people represent 4% of the population, but they make up more than a quarter of all inmates in federal prisons.

At least one local police service was found to be 40% more likely to pull over an indigenous driver than a white one.

In 2015, the Commissioner of the Royal Canadian Mounted Police (RCMP), Bob Paulson, said: “There are racists in my police force. I don’t want them.”

Detective Lorimer Shenher has been a City of Vancouver police officer for 24 years. Referring to police failures around Amber Tuccaro’s case he says, “This is a template that you could drop down on literally hundreds of investigations across this country.”

RCMP Super Intendant Gary Steinke disagrees, saying, “When we go through the cases of murdered indigenous women, by far the majority have been solved.

“Mistakes are made, and the RCMP have learnt lessons. For the Amber case, we have apologised to those involved.”

Statistically, indigenous women are one of the most vulnerable groups in Canadian society.

In 2015, the RCMP released a report which concluded First Nations women are four times more likely to go missing or be murdered than other Canadian women.

According to the report, indigenous women represent 4.3% of Canada’s female population, 16% of female murder victims and 11% of missing person’s cases involving women.

When Europe colonised Canada in the 16th century, the indigenous population was persecuted and marginalised, with communities forced into remote reserves(areas set aside by the government for indigenous communities).

Between 1876 and 1996, 150,000 aboriginal children were taken from their families and interned in boarding schools called ‘residentials’.

These schools were designed, in the words of the system’s founder, Sir John A. MacDonald, to “take the Indian out of the child” – imposing European, Christian values instead.

The reality was often emotional, physical and sexual abuse. Kids were often repeatedly told they were heathens and savages. The residential schools were eventually abolished, with the last one closing in 1996.

Fast-forward to the modern day, and the effects of generations of discrimination can be seen. Canada’s 1.4 million indigenous population have higher levels of poverty and lower life expectancy than other Canadians. Substance abuse is rife, and rates of suicide among some aboriginal communities are at crisis levels.

In the thousands of documented cases of murdered women, some were simply trying to catch a ride to a doctor’s appointment, or the grocery store, lacking other transport from their remote reserves.

Others had moved into the cities and fallen into prostitution.

One woman, Shelly, works an area in Edmonton, Alberta, dubbed ‘death row’, as so many girls go missing or are found murdered there. Shelley has lost ten friends, including her sister.

She herself had a terribly close call.

“These two guys picked me up. One turned around and said: ‘You’re not getting paid bitch’. He grabbed my hair and started hitting me. They raped me for a couple of hours, then left me for dead in a field. I ran to the highway and flagged a car and the cops came and they took me home.”

Stacey also meets T, 30, who is three months pregnant and working the streets. She’s been working as a prostitute since the age of 10, when her Mum put her to work to fund her drug addiction.

As Stacey reflects: “Often these girls are up against it from the very start.”

The legacy of colonisation has pushed them, over generations, into the most vulnerable pockets of society. Discrimination, or dismissive attitudes from the police, only exacerbates that vulnerability.

The Canadian Prime Minister Justin Trudeau has ordered an investigation last year into the missing and murdered women. Perhaps their devastated families may still get some answers.

As Amber’s Mum says, being a First Nations girl, “Doesn’t make Amber any less of a human being. She was my baby.”

Originally Published:

Credit: https://www.bbc.co.uk/bbcthree/article/d98ccfcb-4f16-4186-803f-4cd88b7d8f43