Bridget Tolley simply wants justice for her mother.

Her life changed on October 5, 2001, when her mother, Gladys, was struck by a police cruiser and killed.

“I started asking for a public inquiry into her death,” Tolley, an Algonquin woman from the Kitigan Zibi reserve in Quebec, Canada, told Vox. “There was so much wrong with the case. They didn’t let the family identify the body. The brother of the cop that killed my mother was put in charge of the investigation.”

She paused. “Would you be okay with that?”

Tolley, who grew up poor, said this sort of tragedy is a fact of life for many indigenous people in Canada — both those who live on reserves and those who move to urban areas. She said when she was a child, her father died after shooting himself in the heart. To cope, Tolley turned to drugs and alcohol, but she became sober after her mother’s death. It was a necessary move, she said, because she was so angry with the police. They blamed her mother’s death on alcohol.

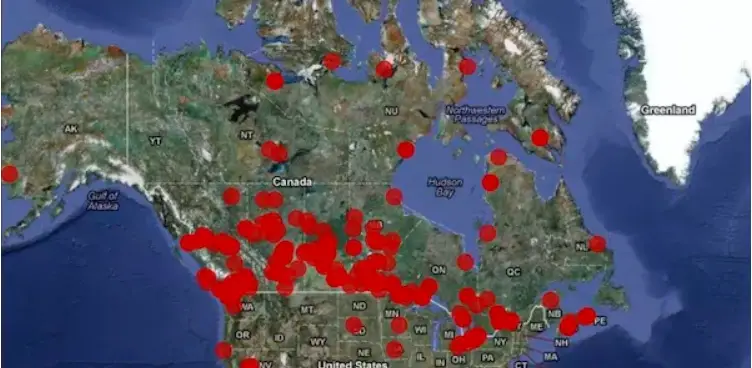

Today, Tolley is a leader in Families of Sisters in Spirit, a grassroots group led by indigenous women dedicated to seeking justice for Canada’s missing and murdered indigenous women. Though indigenous women make up just 4 percent of Canada’s female population, they represent 16 percent of women murdered in the country.

A national inquiry into the missing women, a campaign promise from Prime Minister Justin Trudeau, is finally underway. But many questions remain.

What does “missing” mean in these cases?

Tolley said there are currently two women missing from her reserve. “They went missing in 2008,” she said. “For me, they’re missing. Not kidnapped. Not trafficked. Not until we know for sure.”

Canada’s government defines a missing person as “anyone reported to police or by police as someone whose whereabouts are unknown,” Annie Delisle, head of media relations for the Royal Canadian Mounted Police, told Vox. “They are considered missing until located.”

If the missing person is under 18, Delisle said, she is classified as a missing child and will be considered missing until returned to appropriate care and control.

However, Magen Cywink, an Ojibwe woman of the Whitefish River First Nation, told Vox that finding these missing women has been hindered by police undercounting them in the past or treating cases dismissively. The latter happened when the daughter of one of Cywink’s friends went missing.

“They told [Cywink’s friend] she’d be home soon,” she said. “‘She’s a teenager. She’s out drunk.’ It should be the families who decide who is missing. It should be whenever it’s out of character for the woman to not be in contact.”

Her own sister, Sonya Nadine Cywink, was found murdered at an Aboriginal historic site, Southwold Earthworks, nearly 22 years ago. She was pregnant at the time. The Ontario Provincial Police said she died of blunt force trauma, and no suspects were identified.

“My sister’s murder will probably never be solved,” she told Vox. “I’m not angry. I’m not vengeful. I can’t be. I have to have a clear understanding of what needs to be done.”

Because so many cases concerning missing indigenous women have fallen by the wayside, a need for a community-led database has risen to keep track of these women. Activist groups like It Starts With Us (with which Cywink is involved) and Sisters of Families in Spirit have stepped up to count the women police haven’t identified as missing — women whose cases aren’t being investigated or who go ignored.

When an indigenous woman disappears, the reason is not always immediately apparent. Cold cases abound. Some families have been waiting for more than 20 years and bodies still haven’t turned up. “Missing” is an umbrella term that can encompass them all.

But Tolley said she prefers the term “stolen.”

“They were taken from us,” she said. “They are stolen.”

Read The Full Article At Why thousands of indigenous women have gone missing in Canada – Vox