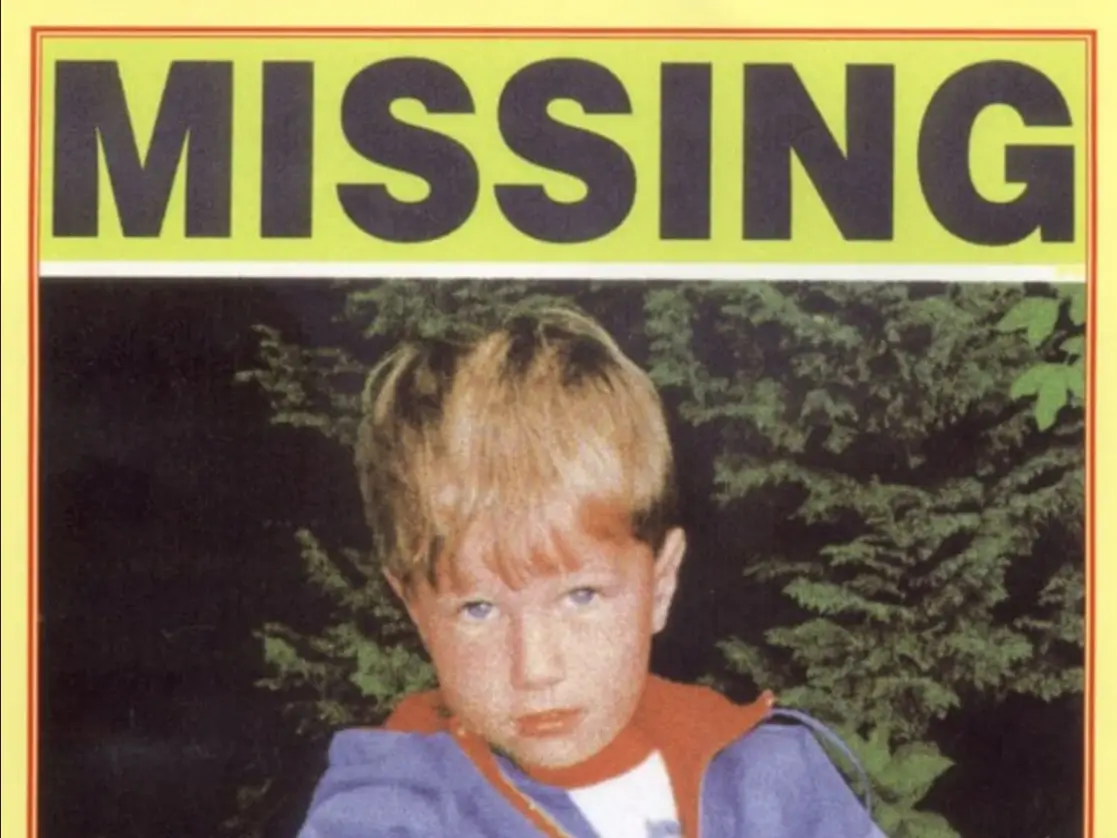

The disappearance of Michael Dunahee is one of the most confounding and unusual missing children’s cases in Canadian history.

Of the more than 50,000 children reported missing in Canada each year, most are found. Three quarters are runaways or “voluntarily” missing and more than half are solved within the first 24 hours, 92% in the first week .

Not Michael Dunahee; the 4-year-old boy who vanished from a playground in Victoria, B.C., in March, 1991. From the outset, the case defied normal investigative techniques: There was no body, no crime scene, not even a verifiable witness — despite police recording more than 50 adults and children present at the flag football event where Dunahee disappeared.

Michael disappeared at the peak of a trend in rising crime that had been hitting Canada since the 1960s. In between 1983 and 1992, Canada’s rate of child abductions increased by 65 per cent. But unlike most of those disappearances, there were no family members within the Dunahee family with designs on abducting Michael. And while B.C. in this era was cursed by the occasional serial killer targeting children, none were known to be in the vicinity of Vancouver Island at this time.

“People were walking around the neighbourhood calling his name, stopping people in the street and asking if they had seen him,” Crystal Dunahee, Michael’s mother, told the National Post. “There were two teams getting off the field and two teams planning to go on. Still — nobody saw a thing.”

This year marks the 30th anniversary of Michael Dunanee’s disappearance, who would now be 34. The interim three decades have yielded almost nothing about his fate and the circumstances of his disappearance, but the case continues to obsess those connected to it for the simple reason that any number of outcomes remain conceivably possible. Michael Dunahee could be alive and well under a false name or his bones could be resting in a shallow grave untouched since the early 1990s.

This is an account of what is known about the disappearance of Michael Dunahee, and what may ultimately unlock the secret of what happened to him.

In virtually every case of a child abduction, the child is taken by a parent or relative. Dunahee remains part of the 0.1 per cent of children missing in Canada who are abducted by a stranger. Even rarer is when children are abducted from what criminologists call their “zone of safety” — anywhere the child is in the immediate vicinity of their parents.

While the search for Dunahee consumed Victoria Police resources in the early 1990s, many of those original investigators are now retired and the hunt remains in the hands of just one officer: Detective Sergeant Michelle Robertson, head of the department’s Victoria Historical Case Unit. She has 33 cases on her desk, including Michael’s.

[ads1]As a case without any scrap of forensic evidence, the Michael Dunahee investigation quickly turned into one of detectives checking out tips from the public. “No body, no crime scene, no witnesses— what does that leave us with? That leaves us with people,” said Robertson.

“There is someone out there that can help us. If you’re not sure and you’re scared, trust in the fact that the truth is the most important thing. That’s all we want — the truth.”

Over 11,000 tips are logged into what’s known as the Michael Dunahee Portal, a custom-built Victoria Police database accessible by a small team of investigators and civilian volunteers. Lately, it’s been racking up leads from the new 24-hour webform tip line launched on the 30th anniversary of Michael’s disappearance.

Robertson reviews each lead, flags duplicate tips and identifies information that is “actionable” such as an alleged sighting. “I take every tip as far as it can go … There’s almost too much information in this case,” said Robertson, who estimated that it would take 5 to 7 years to read the entire paper file. Whenever mysterious human remains are found in the Victoria area, one of the first acts of the police is usually to verify to the public that they aren’t Michael. This occurred as recently as May when a partial cranial bone was found in the city’s Gorge Waterway.

“The minute I start thinking I know what happened to Michael is when I stop looking for him,” she said.

Robertson explained that there are two things that can solve cold cases: A change in technology or a change in relationships. On the technological front, one of the most dramatic examples was the recent arrest and conviction of the Golden State Killer, who went undiscovered for 30 years until investigators used crime scene DNA to track him through a relative who had submitted her own DNA to a genealogical service .

In the case of Dunahee, where there is no forensic evidence, DNA has only served to verify the claims of adults who have stepped forward over the years claiming to be Michael, one of the most recent being a then-26-year-old in Surrey in 2013 .

[ads2]Investigators are now focused on uploading Michael’s DNA profile to international databases as well as Ancestry.com and GEDmatch.com. If Dunahee has grown up as the assumed child of people who abducted him, the idea is that he could find the truth if he ever decides to investigate his family tree. “If Michael was to go search for his ancestry, the connection would be made,” said Crystal.

As for a “change in relationship” that can solve a cold case, one more recent example is that of Kimaya Mobley, a Florida girl who was abducted as a baby. In 1998, Mobley was just a few hours old when she was abducted by Gloria Williams from University Medical Center in Jacksonville, Fla. Williams had just experienced a miscarriage and took Mobley home to her expectant family where the baby was raised as their own.

At age 16, Williams told Mobley the truth as the need for a social security card and birth certificate arose. While Mobley still refers to her abductor as “mom,” Williams is now serving an 18-year prison sentence .

Usually when a child is kidnapped to be raised into adulthood, it’s for much more nefarious purposes than those of Gloria Williams. In 2002, 12-year-old Idaho girl Jan Broberg was kidnapped by her neighbour Robert Berchtold, who then took her to Mexico to marry her before returning the child to her parents five weeks later. Two years later, Berchtold kidnapped her again, where Broberg endured numerous sexual assaults before being rescued by an FBI investigation.

In 2002, 14-year-old Utah girl Elizabeth Smart was abducted by two drifters and held captive for nine months where she was forced to act as a sister-wife of the couple. Eleven-year-old Jaycee Duggard was abducted from a California bus stop just three months after Dunahee’s disappearance in Victoria, but would return to her family 18 years later after being held as a captive of couple Phillip and Nancy Garrido.

[ads3]But nothing about the Dunahee case falls into what the FBI calls “stereotypical abductions”; the small percentage of children taken for sexual gratification.

“The main motive for stranger kidnapping is sexual assault,” University of New Hampshire sociology professor David Finkelhor told A&E Real Crime in 2019 . “Kids who are abducted by strangers tend to be not really young children, but children who may be sought after as a sex object.”

***

According to Crystal Dunahee, on the morning of March 24, 1991, she was the first to rise in her family’s two-bedroom unit in Victoria West, then a working-class suburb mostly populated by the military and young families.

She attended to her six-month old daughter, Caitlin, while making breakfast for her husband, Bruce, and Michael, who had turned four the previous May and was approaching his fifth birthday. A cartoon buzzed in the background as Crystal dressed Michael for what she assumed was going to be a cool day in the park: Teenage Mutant Ninja Turtle t-shirt, rugby pants, and blue-hooded parka. Michael ate a bowl of cereal and played with his neighbour, Ben, before piling into the car with his family. Their destination was Crystal’s first flag football game of the season at Blanshard Elementary School.

Article content

During the short drive to the school, Michael asked if he could go to the playground at the field, and Crystal said she felt a pang of anxiety that she quickly dismissed.

The Dunahees arrived at the field around 12:30 p.m. and Crystal said she told Michael, “OK, you can go to the park, wait there and don’t leave with anybody, just wait there and daddy will come and get you.” She was juggling equipment, a six-month old baby, and an energetic toddler. “It was right behind our backs, a hundred yards away,” said Crystal.

For a split second, Michael leaves her sight, and then, he is gone. “In an instant,” Crystal told the National Post.

Crystal sounded the alarm: First telling Bruce, and then stopping teammates and whoever else was on the scene to tell them that Michael was missing. At 1:05 p.m., Bruce ran to a neighbouring house in order to call Victoria Police.

Within 10 minutes of Michael’s disappearance, the assembled adults and children at the field were all combing the neighbourhood looking for Micheal. Victoria Police officers swarmed the scene and within three hours, they shut down all ferries leaving Southern Vancouver Island and Michael’s face was splashed across the evening news.

[ads4]“It was a crazy scene,” one woman who was there that day told the National Post. “Everything just stopped and people were calling — ‘Michael! Michael!’”

The front page of Victoria’s Times Colonist the day after Michael’s disappearance.

The Dunahees and the Victoria Police did everything right: Authorities were summoned immediately, a description of Michael was disbursed to the media, and a tip line and command post were established within hours. One of the first tips was an alleged sighting from a child, who reported a man in his late 40s in a brown van at the park. “We did put a lot of resources into the brown van tip. In fact we did locate a brown van — a number of brown vans — and we eliminated the owners and drivers through interviews,” now-retired VicPD Detective Inspector Fred Mills told CBC in 2016 . “The brown van was a big thing for a while until we could discount it.”

Hundreds more tips flowed in on that first day, all written out manually on paper.

Most people now working this case knew exactly where they were the day after Michael Dunahee disappeared. Victoria Police’s current spokesperson Bowen Osoko was a teenager delivering the Winnipeg Free Press with Michael’s face on the front page. “There’s something about this file … it is kind of a loss of innocence — not just for people in Victoria and British Columbia but all across Canada. People went ‘uh-oh, if that can happen in Victoria,’” said Osoko.

Actress Winona Ryder was in Victoria filming Little Women when Michael disappeared, and has since publicly expressed an interest in the case. In a 1994 Rolling Stone profile, Ryder can be seen flipping through papers containing details of the Dunahee case.

A few months after Michael was taken, Michelle Robertson — now the chief investigator for the Dunahee case — was a young mother standing outside a Victoria toy store with her son, a little boy with a blond bowl cut, when two police officers approached them. Politely but firmly they separated the pair and asked Michelle “ma’am, is this your child?”

***

[ads5]The Dunahee case is still open, meaning police files are not disclosable to the public, which has only helped to fuel an undercurrent of wild speculation as to his fate.

“I am pretty sure I saw him on a cooking show that was aired out of B.C. That was about two years ago,” wrote Mary Love on one of the many crime blogs on Michael . “He was sacrificed to the Devil,” a Victoria local told the National Post.

Crystal and Bruce were investigated and cleared by Victoria Police early in the case, although they too have found themselves the target of theories.

Speculation can both hurt and help, and the digital age has ushered in whole internet sub-communities of “websleuths” who are occasionally known to crack cold cases.

One of the best examples was when U.S. blogger Joy Baker was instrumental in identifying the killer of Jacob Wetterling, an 11-year old Minnesota boy who was abducted during a bike ride in 1989. Through public crime records and other web-based resources, Baker surmised that Wetterling’s case was linked to the kidnapping and sexual assault of another 12-year-old, Jacob Scheirel. Scheirel then identified his attacker who confessed to killing Wetterling.

According to Valerie Green, author of Vanished: The Michael Dunahee Story , there are three persistent theories in this case. One is that Michael was taken and murdered by a sex offender. Two, he was abducted and raised by a woman or couple who couldn’t have kids. And the final and most dubious theory: That he was killed in a ritual sacrifice — a theory helped along by Victoria being the birthplace of the widely discredited Satanic Ritual Abuse Panic of the 1980s .

Statistics on child abduction and trafficking are very limited in Canada. The RCMP released its first national statistics on missing children in 1987 and on child trafficking only in 2015. “It’s difficult because we don’t necessarily have the statistics that have been consistently kept over the years to allow us to make a connection,” said Lindsey Lobb, a spokesperson at Missing Kids Canada.

But there are documented cases of children under 13 in Canada who vanished without a trace, like Michael, and were presumably taken by a stranger.

In 1958, two-year-old Cindy McLane vanished while playing in the front yard of her home in Willow River, B.C. In 1983, 10-year-old JoAnn Pedersen disappeared from outside a corner store in Chilliwack, B.C. In 1984, Tania Murrell disappeared during the one-and-a-half block walk between her classroom and home in Edmonton, Alta. In 1985, 8-year-old Nicole Morrin disappeared after going to meet a friend in the lobby of her family’s Toronto apartment. All four of these children were never seen again and their cases remain just as cold as Michael Dunahee’s; no body, no crime scene, and no verifiable witnesses.

From what is known from similar cases, if Michael was taken by a stranger it’s likely he never made it off Vancouver Island. According to a landmark U.S. Department of Justice study on missing children homicide , a child taken by a stranger is usually killed within the first three hours of their abduction; 44 per cent within the first hour.

That same study revealed the average perpetrator as male, unmarried and around 27 years old. Half of the killers lived alone or with their parents and were either unemployed or in semi-skilled occupations like construction. The study also revealed that two-thirds of child abductors had committed a similar crime before.

In 51 per cent of cases studied, the perpetrators’ name came up within the first 24 hours of investigation. Most chilling of all, a further 10 per cent managed to insert themselves into the investigation, sometimes posing as helpful citizens to the parents of the child they abducted.

[ads1]Several elements of Michael’s disappearance echo that of Etan Patz, the 6-year-old boy who vanished on his way to a bus stop in the New York City neighbourhood of SoHo in 1979. Patz became famous as the first missing child featured on a milk carton. Like Michael, he too had disappeared while just out of his mother’s sight.

After almost 40 years of investigation and relentless petitioning of the public by Etan’s parents, in 2012 Pedro Hernandez confessed to strangling Etan in the basement of a bodega where he once worked. In 2017, the 56-year-old Hernandez was convicted of kidnapping and murder and sentenced to a minimum of 25 years in jail.

Crystal Dunahee is now the president of Child Find Victoria, an organization that fingerprints children for their parents to keep on file in case they go missing.

When Michael was first taken, the police asked the Dunahees what “level” they wanted to take this to — how much media coverage and exposure, low-key or national. The Dunahees said they wanted to go big as they could make it.

Historic cases are notoriously expensive and will usually peter out without strong public interest. Michael’s case has gotten so far largely because of Crystal’s relentless advocacy.

In March, the Dunahees hosted the 30th annual Michael Dunahee Keep the Hope Alive run — virtually — to raise money for ChildFind BC. They also took part in a press conference at the Victoria Police unveiling of a new age-progressed sketch of Michael.

The Dunahee’s daughter Caitlyn is now 34, and has started a young family. Crystal and Bruce remain married, a rare feat for the parents of a missing child, and are planning their retirement.

Last year, a story out of China electrified the hopes of parents like the Dunahees around the world. After 32 years and 300 false leads, Chinese mother Li Jingzhi was reunited with her son , Mao Yin, who was abducted at age one and sold on China’s infant black market.

For the Dunahees, this case could still have a similar happy ending: An adult Michael raised by different parents with only fleeting memories of his original life in Victoria. As to whether Crystal still believes he’s alive she says “we haven’t been told anything else otherwise.”