Seventeen years ago, the Royal Canadian Mounted Police (RCMP) opened an investigation surrounding nine women and girls who had gone missing or were found murdered along a desolate stretch of roadway in northern British Columbia. The effort was dubbed Project E-PANA, named for the goddess that the Inuit people of Canada believe cares for souls before they go to heaven or are reincarnated.

The number of women that the RCMP identified in its probe soon doubled, to 18, and to keep the numbers from climbing even higher, authorities placed criteria on who would be included on the list. They had to be women or girls, they had to be involved in high-risk activities like hitchhiking, and they had to be last seen — or their bodies found — within a mile or so of Highways 16, 97 or 5 in upper British Columbia.

The Highway of Tears, as the main throughway was dubbed, instantly became a symbol for unchecked violence against Indigenous women and girls in Canada. And it remains a symbol for the violence — and the many reasons behind it — that endures today.

What Is the Highway of Tears?

The drive from Vancouver, B.C., (which is a little less than a three-hour ride from Seattle) to the city of Prince George in northern British Columbia takes nearly nine hours. From there, a western turn along Highway 16 to the port city of Prince Rupert is another eight hours.

It is that final 416-mile (718-kilometer) section of winding, mostly two-lane highway between those two cities — through mountain passes, dozens of tiny villages, countless lakes and a whole lot of wilderness — that has become known as the Highway of Tears.

The remoteness of the highway, coupled with the fact that it bisects so many remote Indigenous communities without access to adequate transportation — often used by young Indigenous women hitchhiking simply as a means of getting from one place to another along the long, lonely road — makes it a ripe ground for violence.

“It’s very, very isolated. You can drive for 15 minutes and not see a car. There are rivers and mountains. It’s very heavily forested,” says Wayne Clary, a retired RCMP investigator who has been brought back to work on the E-PANA cases. “It’s interesting when we look at some of our murders along there and we think, ‘Was this a traveler who came upon this girl and had the opportunity to do what he did, or a local person?’ It’s dark, and the winters are pretty severe. You get a young girl hitchhiking and no one’s around … there one minute, gone the next.”

[ads1]

Giving Names to the Victims

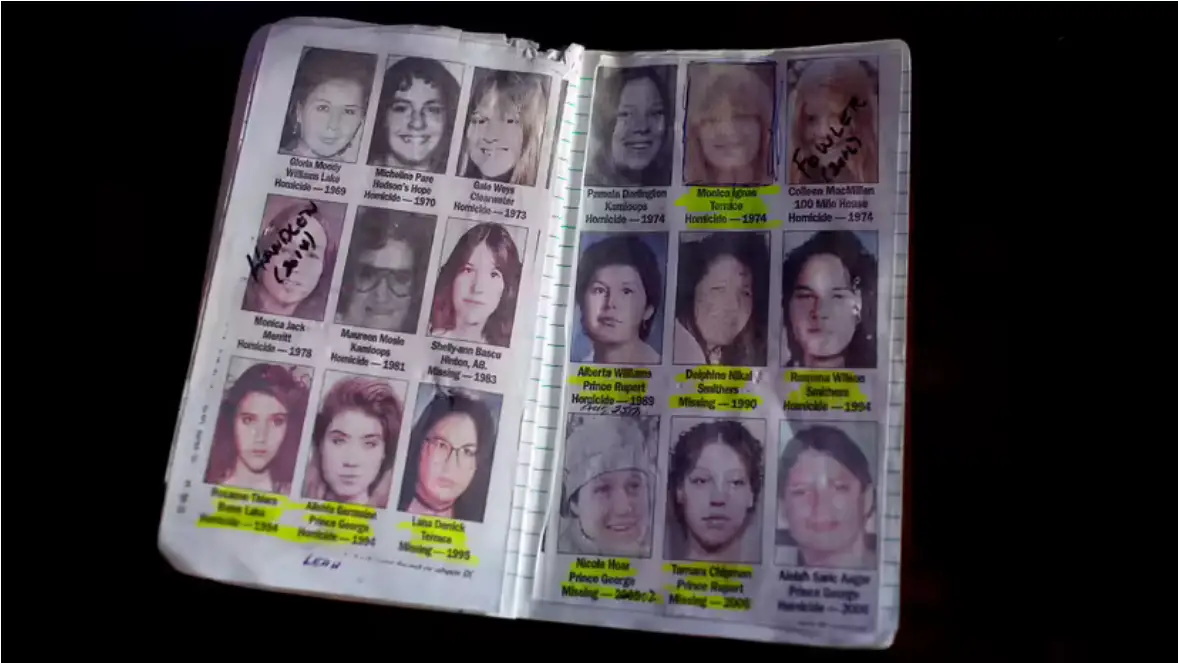

In October 1969, Gloria Moody, a 26-year-old mother of two and a member of the Bella Coola Indian Reserve of the Nuxalk Nation, was found dead along one of the Highway of Tears roads, naked, beaten and sexually assaulted. She became the first of the 18 women identified by the RCMP in the E-PANA project.

Over the next almost 40 years, 17 other women became victims along the highway. The last was 14-year-old Aielah Saric Auger of the Lheidli T’enneh First Nations community, near Prince George. Her almost-unrecognizable body was discovered on an embankment of Highway 16 in February 2006, eight days after she went missing.

At its zenith, more than 60 RCMP investigators worked the cases along the Highway of Tears. But now, more than 15 years after Auger’s body was found, barely a handful of police are still actively involved. No one has been added to the list since Auger, in 2006. Project E-PANA now consists of 13 homicide investigations and five missing people’s investigations.

All the files, officially, remain open. But Clary has been forthright in informing the victims’ families that many of the cases may never be solved.

“We’ve had some success,” Clary says, noting that DNA samples tied notorious serial killer Bobby Jack Fowler to 16-year-old Highway of Tears victim Colleen MacMillen, found dead along the Highway in 1974. Fowler, suspected in at least two other Highway of Tears cases, died in an Oregon prison in 2006, before the connection in the MacMillen case was solidified. In 2019, authorities also got a murder conviction in the case of Monica Jack. The 12-year-old girl went missing in 1978, but her remains weren’t found until 1995. That ruling is under appeal.

“We had a couple of very strong suspects, but just don’t have the evidence. And we’ve used everything in our toolkit that we can,” Clary adds. “I’d say we’ve probably ruled out a lot of bad guys, too. It’s still ongoing, but … a lot of water is under the bridge.”

[ads2]

Getting Legal Justice

Carrier Sekani Family Services (CSFS), based in British Columbia, works to secure social and legal justice for First Nations and other Indigenous families. They began the Highway of Tears Initiative to put into action 33 recommendations made in the 2006 Highway of Tears Symposium Recommendations Report.

The recommendations include measures like better transportation options, increased police patrols, the establishment of awareness and prevention programs among at-risk women and their families, a wide-ranging media campaign and emergency readiness plans.

Yet the violence against Indigenous women, all across Canada, continues. According to the Canadian Femicide Observatory for Justice and Accountability:

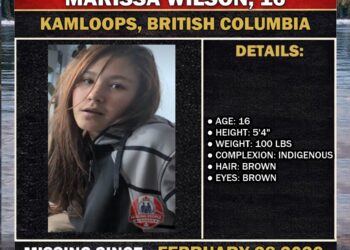

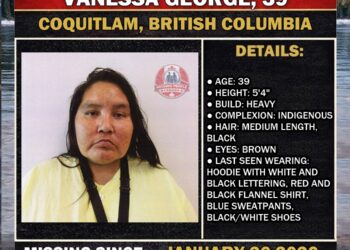

“It’s far too common. Even just this year alone, we’ve had three former clients go missing, you know?” says Elsie Wiebe, the Calls to Justice Coordinator with CSFS’s Highway of Tears Initiative. “Just how common it is for Indigenous women to go missing and be found dead, or not be found at all. It has a devastating impact.”

What still needs addressing, Wiebe and many other Indigenous peoples advocates say, are the underlying conditions that lead to the violence. A 2019 report from the National Inquiry into Missing and Murdered Indigenous Women and Girls put it this way:

Project E-PANA has been the highest-profile police investigation involving missing and murdered Indigenous women and girls, yet it touches on only a tiny fraction of the problem. Reliable statistics are difficult to come by, but more than 2,000 Indigenous women and girls in Canada have been reported to have gone missing or been murdered in the past three decades.

Some are poor or undereducated, victims of domestic violence, drug abusers or are otherwise struggling in a larger society in which they are too often viewed as outsiders in their own lands. But Wiebe says that kind of lazy descriptor is unfair and devalues the defining characteristics of Indigenous communities who have survived immeasurable oppression, racism and targeted violence.

“The women and girls we’ve lost along the Highway of Tears were stopped short in the middle of their goals, dreams, education or careers. They all had full lives ahead of them and they leave behind loving families and friends who continue to look for them and wait for their return. Families and whole communities mourn them dearly,” says Wiebe. “Too often those who are missing or were murdered are unfairly framed as drug users or people in poverty living risky irresponsible lives and this negative stereotyping is not the true story or lived experience of those who we are missing. If the lives of each of these Indigenous women and girls had not been interrupted and taken, some would today be our teachers, psychologists, doctors, mothers, sisters, aunties, daughters, grandmothers, wives.”

Says Wiebe: “I think it’s really easy for people to think that there’s something lacking in these people. Well … it’s what we stole. It’s time to reexamine how we set up these people to ensure that they fail.”

[ads3]

Today Along the Highway of Tears

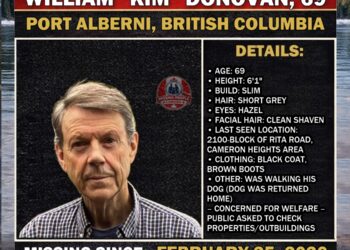

These days, billboards dot the shoulders of the Highway of Tears, warning against hitchhiking, even as the practice remains, to many underserviced Indigenous communities, a primary and necessary means of travel. Clary and other law enforcement authorities continue to talk to the media and work the Highway of Tears cases, hoping that someone, somewhere saw something or heard something and will come forward.

CSFS has recently been awarded new funding in its efforts to support families of currently missing women and girls and others affected by violence against women. May 5, 2022, will again be a national day of awareness for Missing or Murdered Indigenous Women and Girls (MMIWG) in Canada.

Meanwhile, the Highway of Tears rolls on, a tragic and lasting symbol of a problem that stretches across the width and breadth of Canada, and much of the world.

“It’s not just Canada. It’s not just North America,” Wiebe says. “We need to be aware of how residential schools [the nearly century-long system that the government used to indoctrinate Indigenous children into European/Christian culture in Canada] and colonialism are not a thing of the past. There’s still work to be done to undo those colonial practices. There’s still policies that are absolutely unfair and biased against Indigenous people. We need to look at that … and we need to really see and respect Indigenous people and families for their strength and beauty and resilience. We all need to take a personal look at ourselves, and identify the ways that we have bias and behaviors that are discriminatory.”

Source: https://people.howstuffworks.com/highway-of-tears-news.htm